theartofmann

Unveils Noir et Blanc:

A Bold Exploration of Identity, Memory, and Power

theartofmann’s new series, Noir et Blanc, delves into themes of identity, surveillance, and existentialism through striking black-and-white mixed-media works. Presented on expansive sheets of 98lb mixed-media paper (48” x 84”-96”) and suspended from cables, the pieces float, their surfaces shifting with the slightest movement of air. This presentation mirrors the ephemeral nature of memory and the delicate construction of identity in a fragmented, hyperreal world.

The series title references Man Ray’s Noire et Blanche, extending its exploration of perception, identity and stark contrasts of black and white. Layering pencils, charcoal, ink, paint, and solvent transfers of digital archival materials, each piece combines bold gestures with intricate details, embodying the interplay of permanence and impermanence within history and personal narratives.

Each work draws inspiration from French intellectuals and their philosophies. Structures Cachées visualizes Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology with interconnected symbols. Récits Dispersés evokes Michel Foucault’s panopticon through scattered eyes symbolizing surveillance. Horizons Absurdistes reflects Albert Camus’s absurdism, depicting the search for meaning in an indifferent universe, while Dans le Vide de l'Existence channels Sartre’s existentialism, presenting fragmented forms adrift in a void.

In the gallery, viewers are invited to move around the suspended works, observing how light, shadow, and motion interact with their fluid and delicate surfaces. The tactile depth of layered marks reveals a dialogue between deliberate craftsmanship and the unpredictability of chance.

Noir et Blanc is a poignant visual journey, transforming ephemeral marks into enduring reflections on identity, memory, and the forces shaping our reality.

“L’homme est condamné à être libre. (Man is condemned to be free.)”

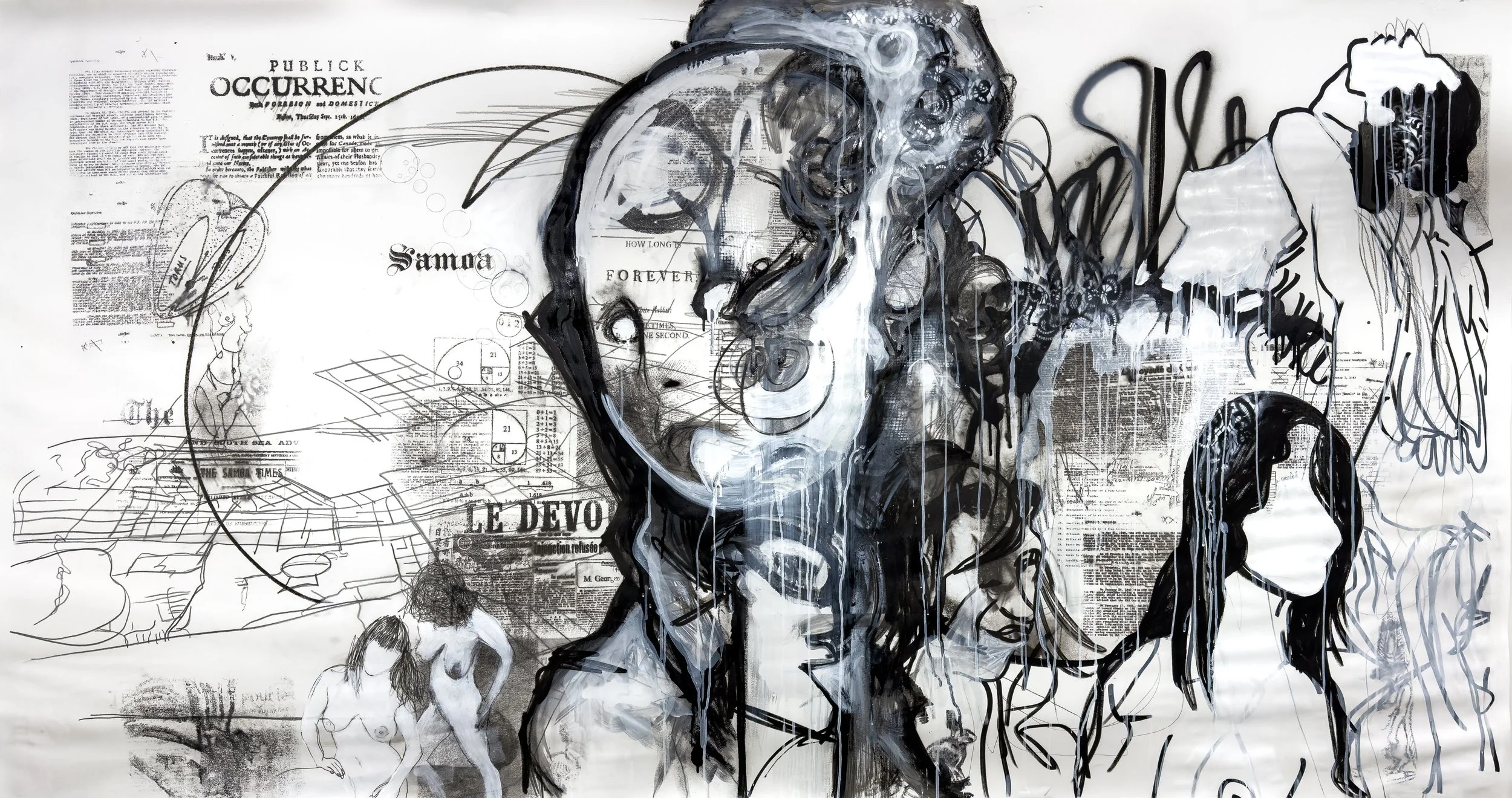

Le Moi Autre

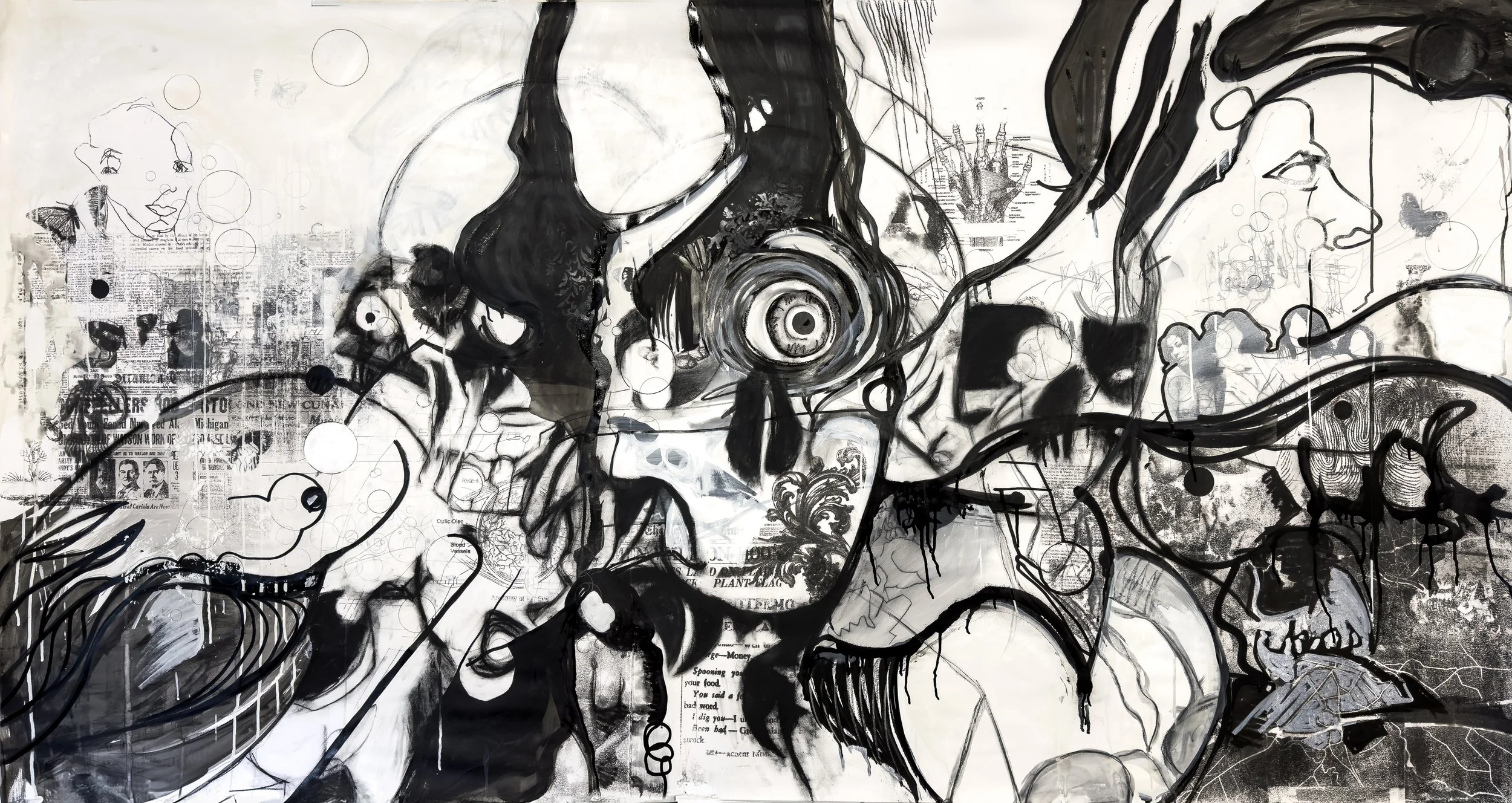

Échos du Tabou

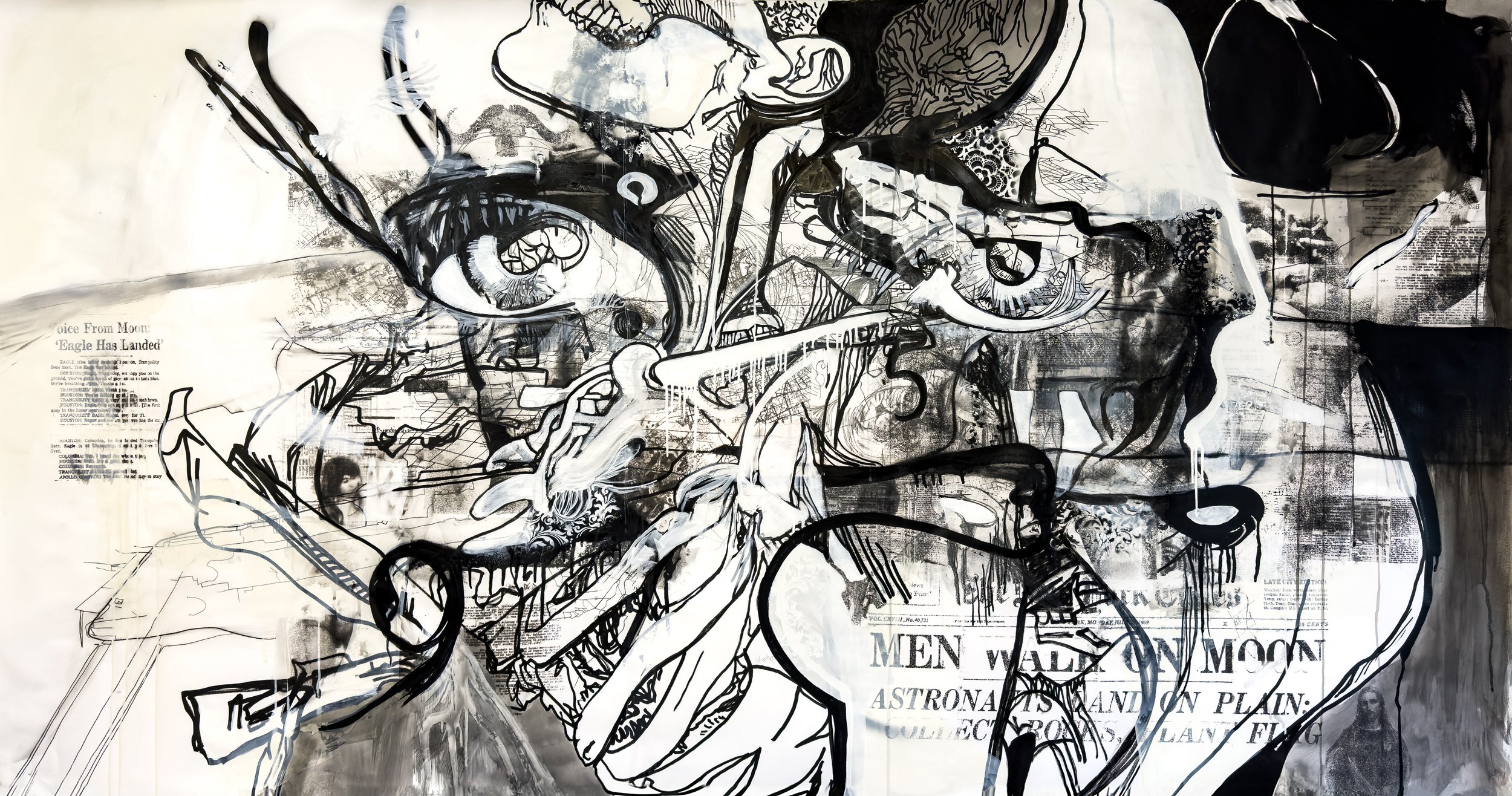

Dans le Vide de l'Existence

Strates du Savoir

Récits Dispersés

The Noir et Blanc series by theartofmann is a visually arresting and intellectually layered collection that interrogates themes of identity, power, memory, and the human psyche. Inspired by Man Ray’s iconic Noire et Blanche, which juxtaposes a woman’s face with an African mask, the series transforms this imagery into a symbolic, abstracted meditation on existence. By shifting away from specific representations, Noir et Blanc explores the universality of these themes, examining the human condition through a purely monochromatic lens. The stark interplay of black and white reflects existential dualities: presence and absence, self and other, light and shadow. Each monumental piece—48” in height and spanning up to 96 inches in length—invites viewers to immerse themselves in intricately layered textures and fragmented forms that challenge perceptions of reality.

Crafted on heavy mixed-media paper, the series employs a wide range of materials, including pencils, charcoal, ink, graphite powder, spray paint, and oil bars. These are combined with a solvent transfer technique, which incorporates degraded imagery sourced from newspapers, FOIA documents, and personal archives. This process creates ghostly, spectral forms that suggest the impermanence of memory and the transience of historical narratives. The faceless, fragmented figures—recurring motifs throughout the series—speak to the tension between self-definition and the external forces that shape identity. André Breton’s surrealist declaration, “La beauté sera convulsive ou ne sera pas” (Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all), resonates in these compositions, where fragmented imagery blurs the boundary between dream and reality, evoking the unconscious forces that underpin human existence.

Philosophical ideas from French intellectuals permeate the series, providing a rich conceptual framework. Michel Foucault’s notion that “La visibilité est un piège” (Visibility is a trap) informs works like Récits Dispersés (Scattered Narratives), where scattered eyes evoke both the internalized gaze of self-regulation and the omnipresent forces of societal surveillance. In Structures Cachées (Hidden Structures), Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology takes form in densely interconnected imagery that symbolizes the universal patterns underlying human behavior and culture. Meanwhile, the chaotic forms of Horizons Absurdistes (Absurdist Horizons) reflect Albert Camus’s philosophy of the absurd, embodying his belief that “Le combat lui-même vers les sommets suffit à remplir un cœur d’homme” (The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart). These works suggest the relentless human pursuit of meaning within an irrational and indifferent universe.

The monochromatic palette, far from being a mere stylistic choice, is essential to the series’ philosophical depth. The stark contrast recalls Picasso’s Guernica, emphasizing the raw emotional impact of black and white, while also drawing from Man Ray’s haunting tonal tension. By grounding its visual language in French intellectual and artistic traditions, the series aligns with a legacy of thought that uses art as a vehicle for questioning fundamental aspects of life. As viewers navigate the layered symbols, spectral imagery, and abstract forms, they are drawn into a dialogue about the fractured, fluid nature of identity and reality. Camus’s assertion that “Il n’y a pas de soleil sans ombre, et il faut connaître la nuit” (There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night) serves as a guiding metaphor for the series, underscoring its exploration of existence as an interplay of contrasts—noir et blanc.

"Structures Cachées" (Hidden Structures) explores the unseen frameworks of human culture through a striking contrast between a structured group of figures and fluid, chaotic abstraction. On the right, faceless figures are tightly grouped, their anonymity suggesting themes of collective identity and the dissolution of individuality within societal patterns. These ghostly forms evoke shared memory and cultural inheritance, aligning with Claude Lévi-Strauss’s assertion, “Les sociétés humaines se construisent toujours rétrospectivement leur passé” (Human societies are always retroactively constructing their past). The figures, bound together yet indistinct, embody the tension between personal identity and the larger cultural forces that shape it.

On the left, fragmented faces, swirling lines, and layered symbols dissolve into a textured cascade of visual elements, evoking the subconscious and ephemeral emotions tied to human connection. A large circular form, reminiscent of a moon or an omnipresent eye, presides over the scene, suggesting cycles, observation, or a higher force connecting the physical and spiritual realms. Embedded within the collage are fragments of text, diagrams, and spectral imagery, which ground the piece in historical and mythological memory. The interplay of order and chaos across the composition echoes Lévi-Strauss’s belief that “La pensée mythique progresse toujours de la conscience des oppositions vers leur résolution” (Mythical thought always progresses from the awareness of oppositions toward their resolution). Through its intricate layering and abstract forms, the piece invites the viewer to consider the cultural structures that persist beyond individual lives, shaping human behavior and perception in unseen but profound ways.

Horizons Absurdistes (Absurdist Horizons) visually embodies Albert Camus’s philosophy of the absurd, portraying the tension between the human desire for meaning and the chaotic indifference of existence. At its core is a spectral face adorned with intricate, ritualistic markings, suspended in a liminal space between identity and erasure. Surrounding it, cascading drips of black paint evoke the uncontrollable flow of memory and emotion, creating a visceral sense of weight and decay. Fragments of text, maps, and diagrams weave through the composition, suggesting futile attempts to rationalize a world that resists coherence. These elements echo Camus’s words: “Le monde en lui-même n'est pas raisonnable, c’est tout ce qu’on peut dire” (The world itself is not reasonable, that’s all that can be said). The interplay of chaotic forms and fragmented symbols evokes a disjointed reality, as if peering into the remnants of human consciousness grappling with its place in the universe.

Faceless, hollow outlines of human figures punctuate the composition, symbolizing the transient nature of identity and the fragility of existence. In the bottom right corner, three faintly drawn figures lean toward one another in a subtle, intimate gesture, offering a fleeting reprieve from the work’s overarching themes of isolation and disconnection. This moment of quiet connection resonates with Camus’s reflection: “Au milieu de l’hiver, j’ai découvert en moi un invincible été” (In the depth of winter, I discovered within me an invincible summer). The fragmented and layered imagery invites viewers to confront the absurdity of their own search for meaning while embracing the beauty in life’s incoherence. This evocative piece, like the philosophy it draws upon, resists easy interpretation, leaving space for reflection on memory, identity, and the human condition.

Le Regard Lié (The Bound Gaze) explores themes of perception, memory, and identity through a dense, layered composition inspired by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. At its center, a fragmented face dissolves into swirling lines, textured shadows, and fragmented text, evoking the elusive, ever-shifting nature of the self. Textual elements such as “How Long Is Forever” and “Le Devoir” (The Duty) scatter across the surface like remnants of thought, emphasizing the interplay between personal memory and collective obligation. This reflects Merleau-Ponty’s assertion, “Le temps n'est pas une ligne, mais un réseau d'intentionnalités” (Time is not a line, but a network of intentionalities), as the image weaves moments and meanings into a nonlinear, immersive narrative.

Surrounding the central face are abstract and figurative forms that heighten the work’s existential tension. On the right, a faceless figure drips with paint, its anonymity suggesting the dissolution of identity, while two minimal, nude figures below bring a sense of raw vulnerability and embodiment. These elements echo Merleau-Ponty’s notion that “Le corps est notre moyen général d'avoir un monde” (The body is our general medium for having a world), reminding us that perception and identity are deeply rooted in physical experience. The dripping textures, fragmented lines, and layered imagery invite viewers into an active engagement, where meaning unfolds through movement and shifting perspectives, embodying the phenomenological connection between the body, memory, and time.

Anatomie du Doute (Anatomy of Doubt) is a stark, evocative depiction of René Descartes' method of radical skepticism, visually dissecting the self in pursuit of undeniable truth. At the center, a fragmented face—part human, part skeletal—emerges from swirling, chaotic forms, its hollow gaze confronting the viewer with existential intensity. The imagery reflects Descartes' assertion, "Je pense, donc je suis" (I think, therefore I am), with the face symbolizing the dismantling and reconstruction of identity through doubt. The swirling, dissolving lines suggest the instability of thought, while black drips cascade downward like the slow erosion of assumptions, evoking his warning: "Il est nécessaire qu'au moins une fois dans votre vie, vous doutiez autant qu'il est possible de toutes choses" (It is necessary that at least once in your life, you doubt as far as possible all things).

Fragments of French newspaper clippings, including "Le Devoir" (Duty) and cryptic references like "ghosts in space," allude to layers of memory, history, and the metaphysical. These elements anchor the abstracted figure in a broader narrative of collective and individual inquiry, while an esoteric symbol in the upper left corner gestures toward the mystical unknown—acknowledging the limits of rational thought. Thick looping lines encircle the composition, creating a fragile framework that contains the chaos while hinting at its potential to break free. By combining fragmented forms, textual allusions, and stark contrasts, Anatomie du Doute immerses the viewer in Descartes’ philosophical tension between skepticism and certainty, memory and decay, the material and the transcendent.

Le Moi Autre (The Other Self) examines identity through a fragmented lens, drawing on Simone de Beauvoir’s concept of “the Other” from The Second Sex. A central eye, unyielding and watchful, anchors the composition, embodying both the act of perceiving and being perceived. Around it, fragmented faces, skeletal structures, and swirling abstract forms overlap, creating a sense of disjointedness that reflects the societal forces shaping identity. This echoes de Beauvoir’s assertion, “On ne naît pas femme : on le devient” (One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman), emphasizing the fluid and constructed nature of selfhood. The imagery suggests a tension between autonomy and the imposed expectations of femininity, as if the self is caught between existence and external definition.

Collaged layers of text, including the historic phrase “Eagle Has Landed,” juxtapose monumental narratives with the deeply personal struggle for self-definition. The solvent-transfer technique blurs these elements, giving them a ghostly, fleeting quality, as though identity itself is dissolving and reforming. Bold gestural lines interconnect the chaotic forms, binding them together in a web of memory, perception, and societal constraint. The composition's haunting, ephemeral atmosphere evokes de Beauvoir’s words: “Se perdre dans l'altérité… c'est revendiquer l'autonomie dans l’abandon” (To lose oneself in otherness... is to claim autonomy through surrender). This piece invites viewers to confront the layered, fragmented nature of identity, challenging them to navigate the interplay between societal roles and the ever-evolving self.

La Création du Lecteur (The Creation of the Reader) visually embodies Roland Barthes’ theory of La Mort de l'Auteur(The Death of the Author), transforming viewers into active participants in shaping its meaning. Anchored by a central circular, eye-like structure that symbolizes perception and interpretation, the piece draws the viewer into a layered composition of fragmented faces, flowing lines, and scattered text. These obscured faces evoke fluid identity, while the fragmented text, sometimes legible and often elusive, mirrors Barthes’ assertion that “le texte est un tissu de citations” (the text is a tissue of quotations), derived from many sources but unified only by the reader. The eye motif serves as both a focal point and a symbol of the viewer’s role in constructing meaning, emphasizing Barthes’ claim: “La naissance du lecteur doit se payer de la mort de l’Auteur” (the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author).

The left side features faint newspaper clippings and collaged elements, creating a sense of nostalgia and cultural memory, as if the piece sifts through hidden or forgotten narratives. Bold, sweeping black lines weave through the composition, guiding the eye across a dreamlike terrain of interlocking motifs, where faces and forms dissolve into one another. Circular patterns and delicate linework suggest interconnected thoughts, memories, and perspectives, further emphasizing the artwork’s open-ended nature. Refusing a single, authoritative interpretation, La Création du Lecteur celebrates multiplicity, aligning with Barthes’ belief that meaning is “construite dans l’espace entre le texte et le lecteur” (constructed in the space between text and reader). By inviting the audience to weave their own narrative from its fragmented imagery, the piece transforms the act of looking into an act of creation.

Paysage Onirique de l'Inconscient (Dreamscape of the Unconscious) is a haunting work that plunges the viewer into a surreal landscape shaped by the primal forces of the subconscious. The composition is dominated by fragmented faces, wide, watchful eyes, and skull-like forms, all dissolving into one another in a chaotic interplay of light and shadow. Thick, flowing strokes snake across the image like veins or roots, suggesting organic movement and a world in flux. These elements evoke a sense of unease, where the familiar becomes grotesque, capturing André Breton’s notion that “La beauté sera convulsive ou ne sera pas” (Beauty will be convulsive, or it will cease to be). The result is a mesmerizing tension between life and death, order and chaos, that mirrors the disorienting yet vivid nature of dreams.

Scattered text fragments, obscured by smudges and layers, act like half-remembered whispers from a dream, offering elusive meanings that remain just out of reach. This interplay between text and imagery underscores Breton’s belief in the surrealist “merveilleux” (marvelous), where unexpected juxtapositions inspire wonder and curiosity. The stark black-and-white palette amplifies the intensity of the piece, creating a stark visual language that captures the ephemeral nature of the unconscious. With its fragmented symbols and unsettling forms, Paysage Onirique de l'Inconscient invites viewers to explore the boundary between reality and imagination, embodying Breton’s assertion: “J’ai toujours eu foi dans la rencontre du rêve et de la réalité” (I have always believed in the meeting of dream and reality).

In Échos du Tabou (Echoes of the Taboo), the viewer is drawn into a haunting exploration of the forbidden and the subconscious. A central triangular motif encasing a single, unblinking eye serves as the focal point, radiating an esoteric tension that echoes ancient symbols of omniscience and revelation. Around this eye, fragmented faces, skeletal figures, and symbolic forms dissolve and merge, evoking a dreamlike, fluid reality where boundaries blur and identities are in flux. These elements channel Georges Bataille’s notion that “La vérité a un seul visage : celui d'une contradiction violente” (Truth has only one face: that of a violent contradiction), as the piece juxtaposes the sacred and profane, beauty and grotesque, to delve into the tension between societal order and human transgression.

Layered textures and faint, fragmented text suggest memories and thoughts surfacing from the unconscious, while anatomical diagrams introduce an unsettling clinical precision that contrasts with the organic chaos of the composition. Thick, visceral black lines amplify the primal intensity, while white spaces provide brief moments of visual respite, evoking layers of consciousness overlapping and shifting. This work captures Bataille’s assertion that “Révéler quelque chose de caché, c’est briser ce qui aurait dû rester scellé” (To reveal something hidden is to break open what should have remained sealed), inviting the viewer to confront suppressed desires and forbidden truths. Échos du Tabou plunges us into the liminal spaces of the human psyche, forcing an encounter with the unsettling echoes of what lies just beyond the realm of the acceptable.

Dans le Vide de l’Existence (In the Void of Existence) draws viewers into an intense, unsettling visual field dominated by a spectral, elongated face with hollow eyes, surrounded by fragmented figures and a chaotic swarm of disembodied eyes. The eyes, varying from simple outlines to highly detailed depictions, create an oppressive sense of omnipresent scrutiny, amplifying the tension between visibility and isolation. This central figure’s emptiness evokes Jean-Paul Sartre’s assertion, “L’homme n’est rien d’autre que ce qu’il se fait” (Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself), as it seems suspended in an undefined space, its identity perpetually in flux. Around it, dark, dripping lines and melting forms suggest dissolution, instability, and the fragility of existence, embodying the existential struggle to construct meaning amid ambiguity.

The composition is further layered with fragmented text, numbers, and abstract shapes, evoking fragments of advertisements, documents, or urban detritus. These elements create a collage-like texture that mirrors the cacophony of modern life and the breakdown of coherent meaning. Words and numbers, partially legible but distorted, hint at societal roles or messages that remain undefined, reflecting Sartre’s notion that individuals are “condamnés à être libres” (condemned to be free)—cast into a world devoid of inherent meaning, tasked with defining their essence. The ghostly faces and fragmented forms seem caught between life and death, confronting the transient, fluid nature of identity and existence. Through its haunting imagery, Dans le Vide de l’Existence invites the viewer to confront the freedom—and weight—of defining oneself within an indifferent and chaotic universe.

Strates du Savoir (Layers of Knowledge) presents a haunting, fragmented exploration of memory, identity, and the passage of ideas through time. At its heart, an elongated, spectral figure with hollow, mask-like features draws the viewer’s gaze, its expression both melancholy and introspective. Surrounding this central figure, disembodied faces and ethereal forms emerge and recede within the dense, chaotic layering of the composition, evoking the ephemeral nature of memory. In the top right corner, an Egyptian bird hieroglyph introduces an ancient, timeless element, offering a stark contrast to the surrounding decay. Partially obscured text reading "Flowering of the Grotesque" underscores the tension between beauty and disintegration, while the hieroglyph invites reflection on transformation and resilience amidst disorder.

The title, Strates du Savoir, resonates with Michel Foucault’s concept of knowledge as a layered and fragmented structure. Fragments of text, interwoven into the background, resemble partially erased records of thought, echoing Foucault’s assertion: “Le savoir n’est pas fait pour comprendre ; il est fait pour trancher” (Knowledge is not made for understanding; it is made for cutting). This interplay of obscured and legible elements invites viewers to engage in an archaeological process, excavating meaning from the piece’s intricate strata. Much like Foucault’s notion of overlapping, contradictory discourses, the composition resists revealing a singular truth. Instead, it offers a complex, shifting tableau of symbols and fragmented ideas, challenging the viewer to navigate its depths and confront the dissonance between memory, identity, and the passage of time.

Lignes Sans Hiérarchie (Lines Without Hierarchy) reflects the philosophical concept of the rhizome by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, presenting a network of faceless, interconnected figures that blur the boundaries between individual and collective identity. The figures, emerging and dissolving into one another, evoke the fluidity of memory and the interconnectedness of human experience. The word "sympathi," prominently placed across the lower portion, anchors the work in themes of empathy and shared understanding. As Deleuze and Guattari assert, "le rhizome n'a ni début ni fin; il est toujours au milieu, entre les choses, inter-être, intermezzo" (the rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo), the composition captures this sense of perpetual connection and movement.

Circular patterns, mandala-like symbols, and collaged text in the upper section evoke layers of spirituality, subconscious thought, and ritual, creating a space where individual identities dissolve into a shared, universal consciousness. A figure with a face obscured by text suggests hidden narratives or suppressed identities, contrasting with the surrounding faceless forms to emphasize the tension between the personal and the collective. The fragmented, distressed textures and faint imagery throughout the piece suggest the erosion of memory and time, creating a visual map of lived experiences rather than a fixed narrative. The fluid interplay of abstraction and detail invites viewers to explore the interconnected relationships at the heart of existence, affirming the idea that each point in this network holds equal significance.

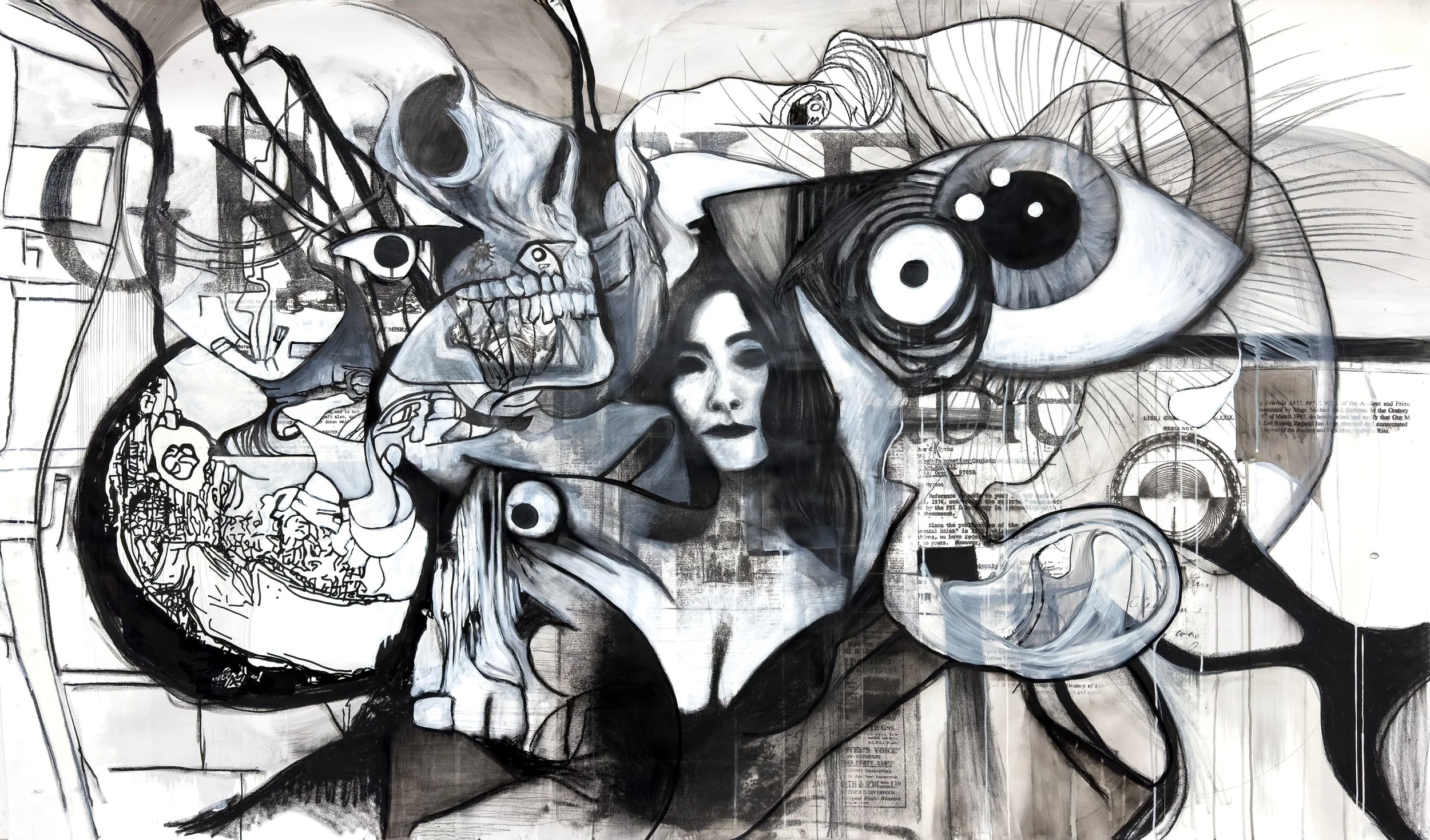

Fragments du Miroir (Fragments of the Mirror) explores the fractured, evolving nature of identity through a surreal and introspective composition inspired by Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis. A skull dominates the left, its hollow sockets and closed mouth serving as a memento mori, blending into chaotic, abstract forms that suggest the dissolution of the boundaries between life and death, self and other. At the center, a woman’s face emerges, her ghostly expression calm yet disquieting, as though she exists both within and apart from the composition. Her fragmented presence echoes Lacan’s “stade du miroir” (mirror stage), where the self is first encountered as a unified reflection but is, in reality, fractured and shaped by external influences.

A large, intrusive eye looms on the right, its exaggerated form a haunting representation of Lacan’s concept of the gaze. “Le regard est au-dehors; je suis regardé, c’est-à-dire, je suis tableau” (The gaze is outside; I am looked at, that is to say, I am a picture), Lacan once wrote, and here, the eye symbolizes a force that sees and shapes identity beyond one’s control. Fragmented text and architectural lines weave through the piece, resembling the scaffolding of memory and thought, while the interplay of mechanical and organic forms reflects the tension between order and chaos. Through its layered composition and interplay of haunting imagery, the piece challenges viewers to confront the impermanence and complexity of identity, revealing the self as an intricate network of internal and external forces.

Récits Dispersés (Dispersed Stories) reflects François Lyotard’s postmodern philosophy, rejecting singular narratives in favor of fragmented, coexisting perspectives. A starkly rendered skull dominates the composition, its exaggerated, disjointed eye symbolizing fractured observation and the instability of identity. Surrounding it, faceless figures and abstract, spectral forms fade and overlap, evoking the transient and elusive nature of memory. Layered throughout the piece, fragmented text—featuring words like "RELIGION" and "ON HUMAN"—interrupts the imagery, inviting existential questioning. As Lyotard wrote, “Nous n’avons plus foi dans les grands récits” (We no longer believe in the great stories), a sentiment visually echoed in the incomplete phrases and disconnected imagery that resist unifying interpretation.

Chaotic and multi-layered, the composition employs jagged lines, dripping paint, and solvent transfers to create a textured palimpsest of fractured meanings. The lower half reveals blurred faces and ghostly silhouettes entangled in abstract lines, suggesting the struggle for connection amidst isolation. The interplay between disintegration and cohesion, decay and permanence, mirrors Lyotard’s view that “la réalité est fragmentée et construite” (reality is fragmented and constructed). In its dense, layered imagery, Récits Dispersés challenges viewers to navigate a world of ephemeral truths and shifting identities, offering a meditation on the nature of human experience and the multiplicity of narratives that shape our understanding of existence.

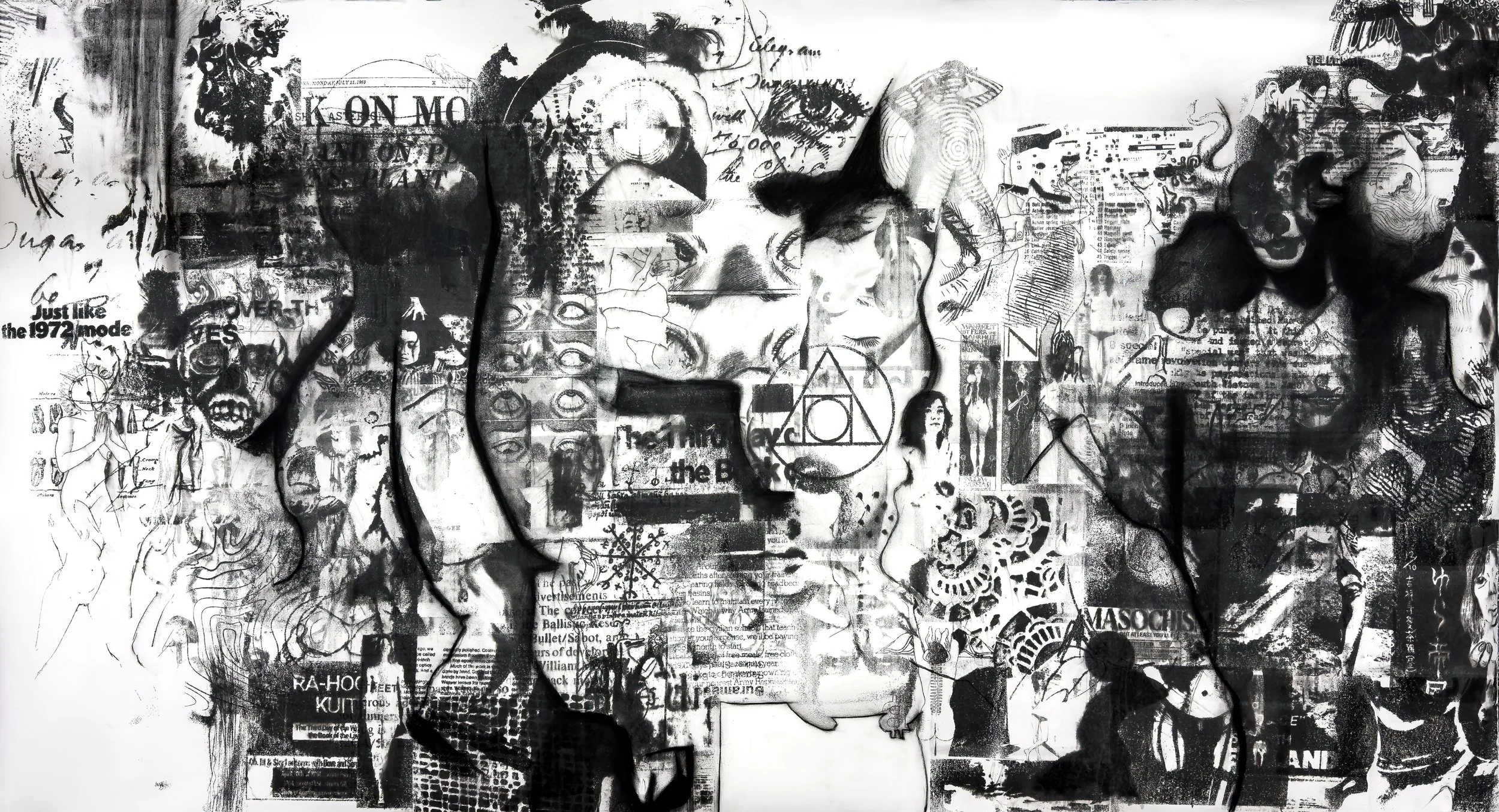

L’Effondrement de la Structure (The Collapse of Structure) is a haunting visual exploration of fragmentation and instability, inspired by Jacques Derrida's philosophy of deconstruction. The artwork features a central, ghostly human form that dissolves into a chaotic web of overlapping imagery, text, and symbols. Faces, anatomical illustrations, and recurring eyes emerge and disappear, creating a sensation of surveillance and fractured identity. Text fragments like “masochist,” “1972 mode,” and “RA-HOOR-KHUT” are scattered throughout, their meanings elusive, evoking a collision of mysticism, rebellion, and cultural memory. The piece resists traditional structures, instead presenting a raw, layered field where meaning is fragmented and deferred, echoing Derrida’s idea: “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (There is no meaning outside of context).

The densely layered textures, formed with bold black lines, ink blots, and fading transfers, suggest an excavation of memory and cultural detritus. Each element functions as a trace, a remnant of a larger narrative that remains incomplete. The chaotic arrangement mirrors Derrida’s “différance”, the perpetual deferral of meaning, as the interplay of imagery and text destabilizes any singular interpretation. Faces are distorted, words obscured, and forms dissolve, embodying the collapse of fixed structures and identities. As the layers refuse to cohere, the viewer is drawn into an unsettling reflection on the instability of self and the impossibility of definitive understanding, where “La signification est toujours en retard” (Meaning is always delayed).